|

With all his beauty and gentle, companionable ways, the Borzoi

is by instinct, breeding and character a coursing hound. In 19th

Century Russia, before dispersion of the estates, Borzoi were

kept by the aristocracy to hunt wolves. Following is Mr. Joseph

B. Thomas' description of the hunt he attended in 1903, during

his visit to Russia, with His Imperial Highness the Grand Duke

Nicholas:

The hunting preserves of the Grand Duke Nicholas extended

over two hundred thousand acres. The establishment of the Grand

Duke was laid out in 'the grand manner'; the ten individual stucco

kennels for the Borzoi, each with a grass court, flanked the

dip of a valley aligned with the magnificent hunting lodge of

Italian architec-ture. At the far end of the valley, the foxhound

kennels designed in keeping with the lodge completed the rectangle....

On his enormous estate of Perchina, the hare, the fox, and.the

wolf are preserved with the greatest care. The three hundred

Borzoi and hundred couple of foxhounds are kept in the most perfect

manner, trained and fitted for their work with the discipline

and individual attention practiced in a racing stable.... The

Grand Duke's Borzoi are exclusively the ancient type hounds.

There are two distinct methods of hunting: one, called field

hunting, where the huntsmen, mounted on ponies, proceed in a

long skirmish line across the open, fenceless country, slipping

their hounds on whatever jumps up. They advance at a walk or

slow trot, in a half-moon-shape skirmish line, about two hundred

yards apart. Another distinctly different method is that of stationing

on all sides of a covert mounted huntsmen with Borzoi in slips.

If wolves are likely to be found, two dogs and a bitch make 'the

team'. Hare and foxes are more often coursed than wolves; but

in each case three different methods are employed to drive the

game from covert. It must be understood that the country is quite

without fences or ditches, with only here and there small groves

of a few acres in extent. The whereabouts of game is usually

reported by the herdsman.

In the early morning may be seen wending its way along the

trail-like rounds of the district, a long line of mounted hunters,

each holding in his left hand a leash of three magnificent Borzoi,

two dogs and a bitch as nearly matched in color and conformation

as possible, and followed by the pack of Anglo-Russian foxhounds,

with the huntsmen and whips in red tunics. On arriving at the

scene of the chase, the hunters are stationed by the Master of

the Hunt at intervals of a hundred yards or so until the entire

grove is surrounded by a long cordon of hounds and riders.  A signal note is heard on a hunting

horn, and with the mingled music of the trail hounds, shouts

of men, and the cracking of whips, the foxhound pack is urged

into the grove in pursuit of hidden game. The scene is certainly

a medieval one. The hunters, dressed in typical Russian costumes,

with fur-trimmed hats, booted and spurred, and equipped with

hunting-horn, whip and dagger, and mounted on padded Cossack

saddles high above the backs of their Kirghiz ponies, holding

on straining leash their long-coated, exceedingly beautiful animals,

make a picture that once seen is not easily forgotten. A signal note is heard on a hunting

horn, and with the mingled music of the trail hounds, shouts

of men, and the cracking of whips, the foxhound pack is urged

into the grove in pursuit of hidden game. The scene is certainly

a medieval one. The hunters, dressed in typical Russian costumes,

with fur-trimmed hats, booted and spurred, and equipped with

hunting-horn, whip and dagger, and mounted on padded Cossack

saddles high above the backs of their Kirghiz ponies, holding

on straining leash their long-coated, exceedingly beautiful animals,

make a picture that once seen is not easily forgotten.

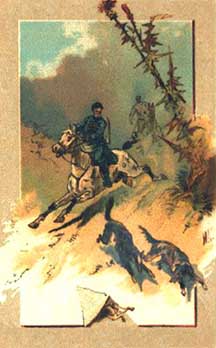

But hark! The sound of hound voices is changed to a sudden

sharp yapping of the pack in full cry, and simultaneously there

springs from the covert a dark grey form bent upon reaching the

next woods, some hundreds of yards away. In an instant he is

well in the open, and sees, only too late, that he has approached

within strik-ing distance of the nearest leash of Borzoi.  With a cry of 'Ou-la-lou', and

setting his horse at a gallop, the hunter slips his hounds when

they view the game, to sight which they oftentimes jump five

or six feet in the air. There is a rush,-a spring,-and with a

yelp the foremost hound is sent rolling; but instantly is back

to the attack, which continues-a confused mass of white and grey,

swiftly leaping forms and snapping fangs-until a neck-hold is

secured by the pursuing Borzoi, who do their best to hold the

wolf prostrate. Then, in a most spirited dash, the hunter literally

throws himself from the saddle of his hunting pony onto the prostrate

wolf. Formerly, a deftly wielded knife assisted in avoiding any

further trouble for the dogs; but of late years it has become

better form to take the wolf alive. A short stick with a thong

at each end, being held in front of the wolf, he seizes it, and

the hunter with instant dexterity, ties the thong behind the

brutes neck. Reynard and the hare are captured in the same manner

by the dogs, but in that case a toss in the air is usually sufficient. With a cry of 'Ou-la-lou', and

setting his horse at a gallop, the hunter slips his hounds when

they view the game, to sight which they oftentimes jump five

or six feet in the air. There is a rush,-a spring,-and with a

yelp the foremost hound is sent rolling; but instantly is back

to the attack, which continues-a confused mass of white and grey,

swiftly leaping forms and snapping fangs-until a neck-hold is

secured by the pursuing Borzoi, who do their best to hold the

wolf prostrate. Then, in a most spirited dash, the hunter literally

throws himself from the saddle of his hunting pony onto the prostrate

wolf. Formerly, a deftly wielded knife assisted in avoiding any

further trouble for the dogs; but of late years it has become

better form to take the wolf alive. A short stick with a thong

at each end, being held in front of the wolf, he seizes it, and

the hunter with instant dexterity, ties the thong behind the

brutes neck. Reynard and the hare are captured in the same manner

by the dogs, but in that case a toss in the air is usually sufficient.

In a few places around the globe, Borzoi are still used as

working hunters, and continue the breed's traditional role as

capturers of large predatory game such as the African hyena.

Similarly, there still can be found in some of the more remote

regions of the U.S. a few Borzoi whose work is to combat the

wolf and coyote marauders of cattle and sheep. But these are

the exceptions in the modern world. The vast majority of Borzoi

are kept as companions, pets, family protectors, show animals,

or occasionally for individual sport hunting.

Text from the "The Borzoi". Blue book published

by Borzoi Club of America in 1973. |